With Japan’s entry into the Second World War in 1941 Japanese Canadians became increasingly aware of their fellow Canadians fear and discrimination. There were calls for their removal from all over B.C. because Euro-Canadians failed to see the distinction between Japanese Canadians and Imperial Japan and projected Japan’s actions on Japanese Canadians intentions.[55] Despite the call for their removal, Japanese Canadians in the Fraser Valley did not face the same level of discrimination as other Japanese Canadians in B.C. because of the communities they had built with Euro-Canadians through their associations.[56]

The Japanese Canadians in the Fraser Valley continued with their daily routines right up until their forced removal from their homes.[57] They saw themselves as an integral part of the community and economy and believed that if they gave into the fear of removal, they would upset the countries social, agricultural and economic stability.[58] Furthermore, despite the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the call for Japanese removal, the Issei and Nisei believed that because they had been participating citizens, benefitted Canada’s economy, had strong economic ties and felt gratitude and trust for the Canadian Government, these factors would win out over the push for their removal.[59] Unfortunately, the Canadian Government officially called for the immediate removal of Japanese, whether citizens or not, anywhere within 160 kilometres of the B.C. coast in February 1942.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941

Image Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/07/world-war-ii-pearl-harbor/100117/

However, Japanese Canadians in the Fraser Valley were not removed from their homes until between April and June.[60] This delay in their removal meant that farmers had time to plant their crops and sell their assets and property. The delay may have been a political move by the government because the Japanese Canadians were such an integral part of the agricultural industry, their sudden removal would have been detrimental.

With the announcement of Japanese removal, neighbors and associations offered to help Japanese Canadians living in the Fraser Valley. The Pacific Cooperative Union (PCU) on March 9, 1942 held a meeting to discuss how they could not only preserve their industry but also aid their Japanese Canadian members. The PCU discussed the legal possibility of Japanese Canadian members transferring their properties and assets to their fellow Euro-Canadian members to hold while they were sent to internment camps.[61] Both the Japanese and Euro-Canadian members believed that this arrangement was the best way to protect Japanese members’ properties and assets.

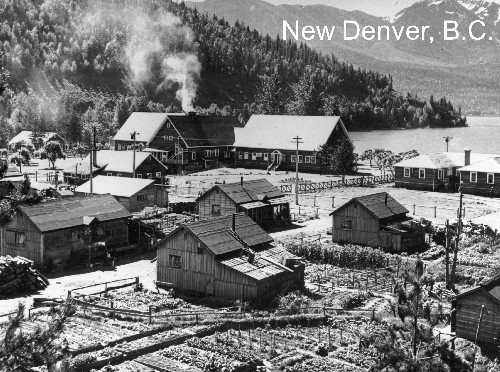

Of all the Japanese removed from the B.C. coast 75% of them were legal Canadian citizens.[62] When the Japanese Canadians of the Fraser Valley were removed from their homes, they were collected by bus and brought into New Westminster where they were put on a train and transported to internment camps.[63] Families were split up. Men of working age were sent to work on railways and farms while the women, children and elderly were kept in separate internment camps.[64] The Japanese in the camps lived in horrible conditions. They were cramped, worked hard and lived in large building where livestock had once lived.[65] Part of the reason for the decision to move all Japanese to the internment camps, separate men from families and spread the Japanese across Canada was to break up the concentration of their communities. The intentional separation of Japanese Canadians limited the danger of them possibly joining forces with Imperial Japan if an attack on B.C. occurred and would also help assimilate them into Canadian culture, which they had been resistant to before.

A Japanese Internment Camp in New Denver, B.C. Image Source: http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/nikkeialbum/items/28/

While the Japanese Canadians were in internment, the Canadian government sold vacant properties and assets of the Japanese Canadians of the Fraser Valley. The Canadians governments selling of Japanese Canadians property went against the promise they made to keep their possessions intact until the Japanese Canadians return following the war. The government would send cheques to the Japanese Canadians as compensation for the sale of their properties and assets, but the value of the cheque was always under the assessed value of what was sold.[66]

The end of the Second World War on September 2, 1945 did not bring an end to the discrimination and hurt that the Japanese Canadians felt. No Japanese Canadians were allowed back within the 160-kilometre radius of the B.C. coast until March 31, 1949, meaning they could not return to their homes.[67] Additionally, when immigration from Japan was allowed to resume in the late 1960’s, political leaders in B.C. wanted entry to be denied to any Japanese immigrant who had been in Japan during the war or were in the Japanese military[68] because of the fear that Japan would attack again. This was a genuine fear in B.C. because when Germany was defeated in the First World War, they were able to start another war 30 years later. B.C. political leaders were still unsure of Japanese Canadians’ loyalties and felt that it was best to delay Japanese immigration as long as possible.

Once the Japanese ban was lifted from the secure zone in B.C., the Japanese were never able to reach the same level of community they had before the war. Many Japanese Canadians could not return to their homes because there was no property to return home to. Japanese Canadians were also spread across Canada. This separation meant that they could not build the same level of community because they were not surrounded by people who shared a language, culture and heritage.[69] Their lack of community and congregation made the Euro-Canadians feel that the threat of Japanese Canadians had gone away.

Many Japanese Canadians felt bitter towards other Canadians and the Canadian Government because the fear and prejudice lingered on following the war. The Canadian government hardly compensated for the Japanese Canadians financial losses. Many Issei and Nisei felt shame because they had lost their property, livelihood and respect in a country many of them were legal citizens in.

On September 22, 1988 Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney gave a formal apology to the Japanese Canadian survivors of the Second World War internment. The apology meant that $300 million was dedicated to reparations. Every living individual directly affected by the internment would receive $21,000 in compensation and the rest would go into a fund to support Japanese Canadians and those who had been charged for refusing to go to interment camps were pardoned.[70]

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney makes an official apology to the Japanese Canadians on behalf of the Canadian Government for their internment during the Second World War. The picture shows Prime Minister Mulroney and the National Association for the Japanese Canadians signing the agreement.

Photo by NIKKEI NATIONAL MUSEUM

Image Source: https://www.timescolonist.com/islander/our-history-righting-a-historical-wrong-for-japanese-canadians-1.23996497

The National Association of Japanese Canadians said that the official apology and compensation package that the Canadian Government gave was a “settlement that heals.”[71] A number of survivor felt that it was too little too late. Many Japanese Canadians who had suffered through internment had died before the official apology. For others they felt that the money and apology did not correct the wrongs or make up for their mistreatment during and after the Second World War.

While not all the survivors of the Japanese Canadian interment felt the apology mended old wounds, it was an acknowledgement of Canada’s past. The Canadian government cannot change the past but with the apology it hoped to mend relationships between the Japanese Canadians and the rest of Canada, own its dark past and work towards a more united future.