The Issei formed tight-knit communities with one another once settled in Canada and were even able to build relationships with Euro-Canadians in the Fraser Valley. Generally, the Issei faced discrimination and had a language barrier between themselves and Euro-Canadians. These factors led to the Issei and their children, Nisei, to form their own communities through common language, experiences, jobs and associations they created in Vancouver, Steveston and the Fraser Valley.[15]

Two organizations that helped the Japanese Canadians create a sense of community with one another were the Kenjinkai and the Nokai. The Kenjinkai was made up of Issei and was put in place to help them find jobs, train them, give financial aid and helped them network with one another.[16] The Kenjinkai also helped by giving aid in times of death or illness and provided financial aid to new single men from Japan.[17] The Kenjinkai was common throughout B.C. but the Nokai was more common in the Fraser Valley. Nokai means an agricultural society[18] and was therefore better suited for Issei who were living in the Fraser Valley as opposed to urban areas like Vancouver, Steveston and Vancouver Island. The Nokai served two purposes. First it helped serve their economic and financial needs by providing supplies, machinery, markets and aid for the farmers.[19] Second, it acted as a supportive and kind community for Japanese Canadians who were not always welcomed by Euro-Canadians.[20]

The Nokai not only benefitted the Japanese Canadians community itself, it helped the Japanese Canadians build relationships with other Canadians in the Fraser Valley. The Japanese Canadians would open up their Nokai halls to the general community for school concerts, graduations, and community dinners and celebrations.[21] These gatherings would bring together Canadians of all ages and ethnic backgrounds, and allowed them to share food, culture and heritage with one another. These gatherings were great for community building between Euro-Canadians and Japanese Canadians and there were never any reports of violence or disagreements at these gatherings. It was because of gatherings like these that the relationship between Japanese Canadians and Euro-Canadians were seen as more positive and less discriminatory in the Fraser Valley than in urban and coastal areas of B.C.[22]

The Issei believed whole heartedly in their children’s education. They believed that it was essential for their children to get both a Western education and a Japanese education. The Nisei’s parents were eager to enrol them into kindergarten and get them to go as far as they could in the Western education system. Many of the schools in the Fraser Valley were one-room school’s with students of all ages in the classroom and mixed Euro-Canadians with other children, such as the Nisei. Through their Western education the Nisei would learn English, how to read and write, math, history, French, etc.[23] The Issei believed that through education their children, who were Canadian citizens by birth, could assimilate and gain cultural understanding that they themselves could not achieve. The Issei thought that the Nisei would be accepted into Canadian culture and receive full rights and opportunities because of their education.[24]

Glenwood School Class photo in the early 1930’s. Japanese students including a child from the Fukumoto family are featured in the photo.

Langley Centennial Museum Photo #2010.022.040

However, Western education created tension between the Issei and Nisei because of the growing cultural divide between the two generations. Through their Western education the Nisei were receiving Canadian names[25] and becoming more comfortable to speak English with their siblings and others than speaking Japanese. Because of this growing tension between themselves and their children, the Issei felt it was necessary and important for the Nisei to learn more about their Japanese heritage,[26] so they enrolled them in Japanese language schools throughout the Fraser Valley. The Japanese schools in the Fraser Valley would bring in teachers and Buddhist priests from Vancouver to teach[27] and the Nisei would attend after their Western school educational hours. The Nisei would learn Japanese, Japanese history and about their parents’ culture and religion.[28] It was through the Nisei’s Japanese education that the Issei felt that they could stay connected with their children and continue to build a strong Japanese community.

Despite the desire to complete their education, there was also the knowledge that the Nisei would have difficulty entering the work force just like their parents.[29] Many Nisei would complete their high school education with the hopes of getting a job but would find that despite their education Euro-Canadians were resistant to hiring them. While education was a tool to help integrate the Nisei into Canadian culture, it was quickly realized that despite having the proper education the Nisei were will seen as less than Euro-Canadians. They were not seen as Canadian enough to get a job.

The workplace in British Columbia was a mix of great opportunity and hard racial discrimination for Japanese Canadians. When the Issei first came to Canada, they were restricted in what industries they were allowed to work, so a majority of them worked in fishing, logging, farming, etc. Generally, the Chinese and Japanese workers were paid about 10 cents per hour making them cheap labour[30] which made them attractive to employers.[31] Workplaces in the Fraser Valley such as the shingle mills and shingle bolt camps, canneries, mines and sawmills were centers for large populations of Japanese employment.[32] While the employment was a good thing for the Issei, the Euro-Canadians were angered by the competition they were facing in the work force. A Maclean’s article made the comment that Euro-Canadians must “wonder why jobs are so scarce for white men while Orientals never lack work when they need it.”[33] Labour competition led to tension and even violence, like the 1907 Race Riots in Vancouver.

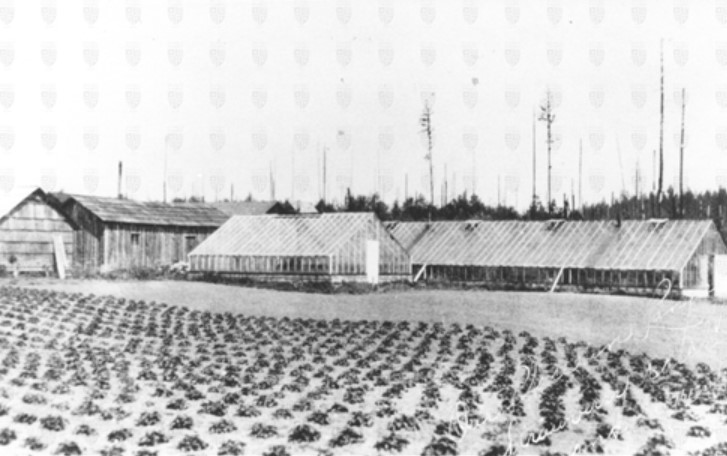

Photo of a Japanese Canadian family farm.

Langley Centennial Museum #3486

The most common industry of work for the Japanese Canadians was farming and it became the industry in the Fraser Valley that led to good relationships with fellow Euro-Canadian Farmers. Many Issei that came to settle in Canada had been farmers in Japan. Farming allowed the Issei to build community with fellow Issei and to get away from discrimination in the work force.[34] Through these farming communities, the Japanese Canadian farmers were finding economic success. Furthermore, they were receiving the respect and admiration of Euro-Canadian farmers for their work ethic.[35] Because of the relationship forming between Japanese and Euro-Canadian farmers in the Fraser Valley, farming associations that included both cultural groups were forming. Groups such as The Rhubarb Growers Association establish in 1925,[36] the Berry Growers’ Cooperative Exchange was created in 1927,[37] and the Pacific Cooperative Union (PCU).[38] All of these farmers associations helped form good relationships and community between the two groups in the Fraser Valley. In hard times such as the Japanese internment, these associations would not only look out for one another but also try to preserve their relationships along with their industry.