Naoyuki “Joe” Fukumoto was interviewed three separate times in 1989[39], 1992[40] and 2011.[41][42]. He was interviewed in his home in Calgary by Warren Sommer. These interviews tell the Fukumoto story and were provided by the Langley Centennial Museum through four recordings.

The Fukumoto Family

Langley Centennial Museum Photo #2010.022.043

The Fukumoto Family were a Japanese Canadian farm family that lived in Fernridge, British Columbia. Naoyuki “Joe” Fukumoto’s father came to Canada around 1907 before the Vancouver Riot to find work following the Russo-Japanese War which was in 1904-05. He worked in a few different industries before settling in the sawmill industry and quickly became one of the best employees. Joe’s mother came to B.C. in 1918 as a picture bride already engaged to marry Joe’s father. Joe was the second child born in the family on August 8, 1922.

Shortly before or after Joe was born, Joe’s father had saved enough money from working in the sawmill to buy the family farm. The farm was located in Fernridge B.C. (modern-day south Langley). The far was 25 acres in total but they only were able to clear 5. They built a four-room shack for their family to live in and the rest was dedicated to farming. They grew asparagus and strawberries and raised about 1200 chickens for eggs all to sell at markets. Joe’s father did not work full time on his farm. During the week he continued to work at the sawmill because despite his race, he was a valued employee because he was a skilled and hard worker. His boss refused to replace him with a Euro-Canadian. He would work on his farm before and after work and on the weekends. Additionally, the Fukumoto children would have chores on the farm before and after school. The family hardly had any time to socialize with neighbors or other children unless they came to the farm to see the family.

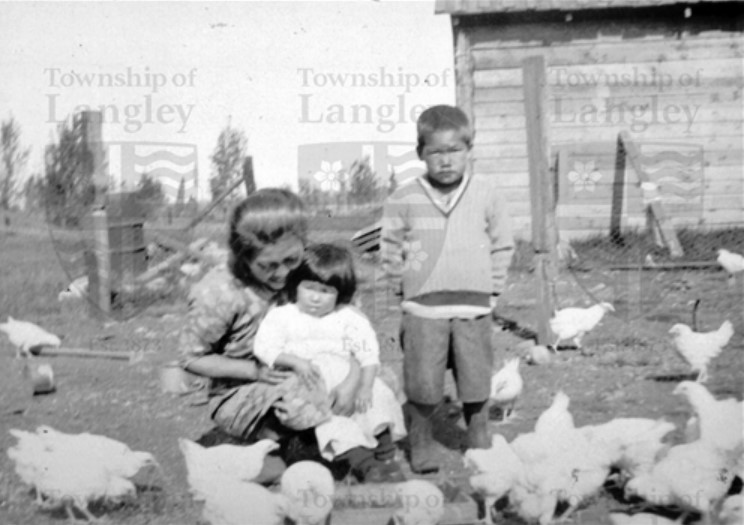

Joe Fukumoto’s mother and two of his siblings on the family farm in 1935.

Langley Centennial Museum Photo #2010.022.041

The Fukumoto family was not the traditional Japanese family. While they did speak Japanese at home and loosely adhered to Buddhist traditions, they were a fairly westernized family. Despite being an Issei, according to Joe, his father was not a member of the Kenjinkai. Additionally, the Fukumoto’s children only received a Western education, went by their English names to everyone except their parents and hardly experienced any traditional religious or cultural practices. Joe’s parents were fairly isolated because they did not speak English very well and hardly socialized with anyone other than the occasional visit from their Euro-Canadian neighbors who were providing help or occasions such as Japanese New Year.

Growing up, Joe did not feel as though he was discriminated against or very aware of the Euro-Canadian tension with Japanese Canadians. He had good memories of being in school and making friends. The neighbors were always kind to his family and would willingly help his parents with anything they did not understand. The only instance of racism that Joe remembered experiencing was shortly after Pearl Harbor was attacked and a drunk man asked Joe “If Japanese come over here would you help them?” and Joe replied no. Then he asked Joe “would you report if you saw someone trying to bomb a bridge” and Joe said he would report it to the police. The drunk man then declared that Joe was alright despite being Japanese.

When the Japanese Canadian expulsion and internment was announced in February 1942, the Fukumoto’s started to sell their livestock. Their neighbors offered to continue to work their farm and send them the money while they were in internment. In May 1942, a bus came to the Fukumoto farm to take them away. Joe recalled that his mother feared internment because of what was happening in Germany to the Jews. They were only allowed to bring 10lbs per person. Because Joe’s father was older than the working age, the family was offered the chance to stay together if they went to Calgary to work on a sugar beet farm. The Fukumoto’s took the offer and boarded the train in New Westminster to be taken to the farm in Calgary.

The living conditions on the farm were not great. When they arrived, they found that their family of seven was to live in a two-room shack (a kitchen and a bedroom) with no insulation, no running water or well and no electricity. The family had to dig their own well and while they dug it they had to get water from the pond that the cows from the farm drunk out of. Eventually the owner of the sugar beet farm did provide lumber for them to add another room to their shack.

While working on the farm they continued to receive money from their neighbor from the profits of their farm, however, within a few months they received a letter from their neighbor stating that he was no longer allowed to send the Fukumoto’s money. Shortly after they received word that the Canadian Government had sold their family farm and sent them a cheque of $1200. Joe recalled that his father was not too upset that the family farm had been sold because the land had not been very good, however, he was upset because the amount the government had sent was below the assessed value of the land.

When the war ended, the Fukumoto’s decided to stay in Calgary because they no longer had a home to return to and their father had a mutual friend in Calgary who offered them work on his poultry farm. Joe’s father also found that other Japanese families had also lost their properties and received less than value cheques. He and other Japanese families decided to not cash their cheques and open a legal battle against the Canadian Government. In the end they won the case and the Fukumoto’s received a $1700 cheque for the loss of their farm.

Following the war, the Fukumoto family never owned a farm again because of the financial loss of their farm in Fernridge. Joe recalled that despite the hardships his family faced, his parents never expressed any bitterness or resentment towards the Canadian Government. Joe’s parents died before the Canadian Government made an official apology to the Japanese Canadians that lived through the internment period. While Joe was indifferent to the apology, he did appreciate the money that he received. Moreover, he also recognized that other Japanese Canadians felt that the apology was too late. Many still felt bitterness and shame because of the internment. Joe expressed that for those people, the apology did not correct the wrongs or make up for their mistreatment.